The Military Voter’s Act of 1917 is one of the most notorious political manoeuvres of the Borden government in the First World War. The act would extend the vote to soldiers families, deny the franchise to certain ethnic groups, and would presumably secure further support for the government. Prior to this monumental legislation, in 1915, the right to vote by mail was given to military members overseas. As Desmond Morton noted that the postal ballot, “excluded women and minors in the CEF from the franchise, allowed soldiers to choose any constituency in which they had spent at least thirty days prior to enlistment or, if that failed, any other.” (Morton, p.131) In 1917, with the Wartime Elections Act and the Military Voters Acts, the vote was given to all active or retired members of the Canadian armed forces, including women, minors, and First Nations. Men who were not landowners, yet had a son or grandson in the forces were extended the franchise, as were women with relatives who were soldiers.

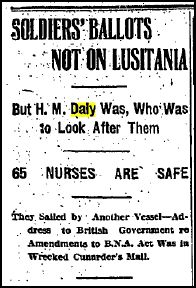

In 1915, an interesting connection between the postal ballot and the sinking of the Lusitania is noted by Morton. He writes, “On 5 May the British cabled their approval but two days later the soldiers’ vote was, quite literally, sunk. Armed with a militia commission and a large supply of ballots, Harold Daly, a former Vancouver lawyer and now a Hughes aide and all-purpose fixer, had embarked on the Lusitania."

|

| The Globe, 8 May 1915, p.7. |

Daly was the son of a former mayor of Brandon Manitoba, and the Daly House there is now a museum. Family lore has recorded his last moments upon the ship, as interpreted here by the Lusitania Resource:

The sinking of the Lusitania inflamed public opinion against the Germans, and served as a major propaganda coup. Posters of women and children sinking in the waters were used for enlistment purposes which channelled the revenge instinct over outrage at the torpedoing of a civilian liner. The attack on the ship has been cited as a cause of the American entry into the war.On the day of the disaster, Daly was playing solitaire, which another passenger had taught him to play. During the last few moments, he bought a cigar from the bartender who told him to get out. No sooner did Daly exit the door of the lounge, the water washed him overboard. He said the curious thing was that he was among a different set of people than who he had seen on deck when the ship sank, to which he attributed to the ship striking bottom, before she sank.